☧

Introduction

Last week, I went out to a bar with some of my coworkers after work. The conversation was cordial and everyone was having a nice time enjoying the happy hour specials. After a while, the conversation started to die down and it looked like everyone was going to pack it up and head home, but out of nowhere, a torrential rain started pouring down. The wind and rain started coming in through the open doors and persisted through the cracks even after the doors were shut. We had all parked several blocks away, so we looked at each other and unanimously decided not to challenge the micro-hurricane and to order another round of drinks instead.

I’ll spare you the details, but three of the six of us who were at the bar are Catholic, and eventually the conversation turned to communion. There was a discussion on communion in other Christian traditions being a symbolic representation of Christ’s body and blood, then the conversation toward communion in the Catholic church. There was some confusion over why non-Catholics couldn’t receive communion if it’s “only the representation” of Christ’s body and blood. Additionally, there was an argument that “it’s really up to me in the end; what I see going on is what’s going on, so it doesn’t really matter if I receive communion in a Catholic church and don’t believe.”

I countered this argument by trying to explain, admittedly not so well, that the bread and wine consecrated in the Mass are substantially and truly changed into the Body and Blood, the real presence of Christ, that we receive in the Eucharist. I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to communicate one of the most substantial and frankly, one of the most deeply unsettling mysteries of the Church in a bar to someone who has never heard this before, but let me tell you from experience, it’s not an easy task.

The aim here is to give proper context to, and the reasoning behind, the Eucharist. It’s a topic which many Catholics understand subconsciously and although it can be a source of great joy and faith for us, sometimes we cannot adequately describe the reasoning behind the practice. In order to share our faith with others, we need to be able to communicate the difficult topics to others, even if we’re doing it in a bar.

Alright, so we have established that when we receive the Eucharist in Mass, we are receiving the body and blood, soul and divinity of our Lord, Jesus Christ. That is to say, by Transubstantiation, the bread and wine are fundamentally and wholly changed into the body and blood of Jesus. The bread and wine are not like the Body and Blood, they are not representative, nor are they symbolic. They are.

Physical Characteristics

Since we insist that we’re actually receiving the flesh and blood of Christ, must we necessarily taste it as flesh and blood? Anyone who has taken communion knows that the answer is no, it doesn’t actually taste like flesh and blood, it tastes like a crunchy little cracker washed down with a sip of wine. It doesn’t mean that you’re a bad Catholic or that your faith isn’t strong enough when it looks and tastes like plain bread and wine. It does, and probably will for the rest of your life. I say “probably” because there have been some recorded instances of the consecrated elements actually-actually turning into flesh and blood – it is always “actually”, but in these cases, it takes on the physical characteristics of flesh and blood. Truly, they are miracles and we will talk about one momentarily. The fact that the Eucharist has the physical characteristics of bread and wine does not make it any less profound. Even if it doesn’t taste like it, we are still receiving the whole Christ, body and soul, when we receive communion. As faithful Catholics, we are given the ability, through faith, to perceive not only with our physical senses, but also with our spiritual senses. We are given God’s grace through the Holy Spirit as we receive Christ in the Eucharist in a Trinitarian act of love, faith, and devotion.

The Miracle of Lanciano

In Lanciano, Italy during the 8th century, a Basilian monk, who was skeptical about the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, was celebrating Mass. After he said the words of consecration, it’s reported that the host was miraculously changed into physical flesh and the wine into physical blood. The Body and Blood were kept in a reliquary and were investigated by the Church and confirmed as a miracle. In 1971, the specimens were examined by Oroardo Linoli who is a professor in anatomy and pathological histology as well as chemistry and clinical microscopy. He found that the Flesh is human cardiac tissue of type AB consistent with the source being of Middle Eastern descent. The Blood, also type AB, was found to contain proteins in normal proportions to that of fresh, normal blood. Their physical condition remains mostly preserved despite the fact that they were left in their natural state exposed to the action of atmospheric and biological agents for twelve centuries, and there were no traces of preservatives detected in the study. The image shows the relics contained in the Ostensorium displayed in the Church of San Francesco in Lanciano, Italy. We don’t have the time to do it here, but I encourage you to research more about this miracle and others like it.

consecration, it’s reported that the host was miraculously changed into physical flesh and the wine into physical blood. The Body and Blood were kept in a reliquary and were investigated by the Church and confirmed as a miracle. In 1971, the specimens were examined by Oroardo Linoli who is a professor in anatomy and pathological histology as well as chemistry and clinical microscopy. He found that the Flesh is human cardiac tissue of type AB consistent with the source being of Middle Eastern descent. The Blood, also type AB, was found to contain proteins in normal proportions to that of fresh, normal blood. Their physical condition remains mostly preserved despite the fact that they were left in their natural state exposed to the action of atmospheric and biological agents for twelve centuries, and there were no traces of preservatives detected in the study. The image shows the relics contained in the Ostensorium displayed in the Church of San Francesco in Lanciano, Italy. We don’t have the time to do it here, but I encourage you to research more about this miracle and others like it.

The Last Supper

Now, let’s turn to the question of why we believe this. When asked about the reason that Catholics do the “Eucharist thing”, I think the easiest answer is Jesus’ words at the Last Supper. The details are told in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and are exemplified here in Mark 14:22-24 (the italicized words, not needed in Greek, are added for English cohesion and grammar):

While they were eating, He took some bread, and after a blessing He broke it, and gave it to them, and said, “Take it; this is My body.” And when He had taken a cup and given thanks, He gave it to them, and they all drank from it. And He said to them, “This is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.

In each of the accounts in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), Jesus is quoted saying that the bread and the wine is his Body and Blood. He does not say the bread “is like” or “represents” or “is only spiritually” his Body. He says, “is”!

At this point, the issue of figurative language will come up; a fair point as there is quite a bit of figurative language present in Scripture, but with this particular event, the language was not figurative. We can turn to Greek, the language in which the gospels were written, for support. From the passage mentioned above, Mark says, “τοῦτό ἐστιν τὸ σῶμά μου,” or phonetically, “Touto estin to soma mou” which translates to, “This is my body”. The Greek verb, ἐστιν (estin), is equivalent to the English word “is” and is grammatically taken to mean “is really” just as “is” in English is usually taken literally. There was no “figurative presence” stated at the Last Supper; it was the real deal. The literal meaning cannot be avoided except through disregard for the text itself and through the rejection of the understanding of the Church Fathers in the early years of the faith. The writings of Paul, John, and many other early Christians reflect belief in the True Presence and there is no legitimate basis to doubt their understanding and interpretation.

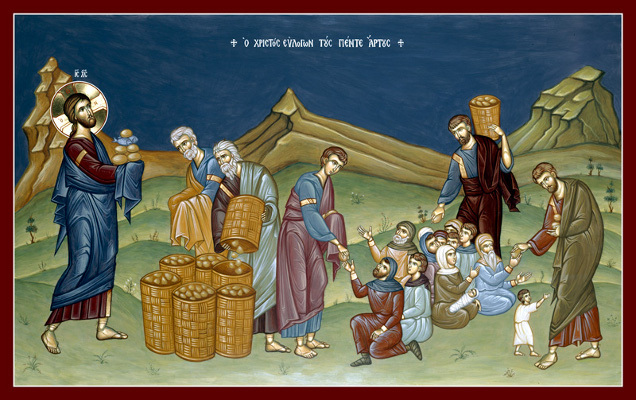

The Bread of Life Discourse and The Words of Eternal Life

The Last Supper is not the only place in the Gospel that we get the idea of the Eucharist. Let’s turn now to the Bread of Life Discourse in John, Chapter 6. This discourse occurs in the synagogue in Capernaum on the day after the Multiplication of the Loaves. I’m not going to quote the whole thing here, but it really is worth a read – it’s short, but very powerful. The part we’ll focus on is this (John 6:51-59):

“I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world.” The Jews quarreled among themselves, saying, “How can this man give us [his] flesh to eat?” Jesus said to them, “Amen, amen, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life within you. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I in him. Just as the living Father sent me and I have life because of the Father, so also the one who feeds on me will have life because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven. Unlike your ancestors who ate and still died, whoever eats this bread will live forever.”

This discourse is a pretext to the Last Supper and, even further, to the Mass which has been celebrated continuously since the institution of the Eucharist. It’s hard to deny the language used in this text even in English, but it’s even harder when we look at the Greek.

In the first line of the above quote, the Greek verb for “eat” used is “φάγω” (phago) which simply means “to eat” as one would eat food. At the incredulity of his followers after this statement, Jesus doesn’t back down with his language, rather he intensifies it. In the following lines, he uses the Greek verb “τρώγω” (trogo) which is a much more graphic form of “eat” and more closely means “to gnaw on” or “to crunch”. These verbs and the transition from “phago” to “trogo” suggest that Jesus was speaking literally about his flesh being the bread of life and that it would be given up for us to consume for us to remain in him, and he in us.

In the next section, The Words of Eternal Life, we see that his disciples are shaken by The Bread of Life Discourse when they say, “This saying is hard; who can accept it?” To the Jews, who were by law forbidden to consume blood (Leviticus 7:10), this speech was incredibly hard to hear combined with the fact that their teacher was telling them that they must eat his flesh. We then see in John 6:66, “As a result of this, many [of] his disciples returned to their former way of life and no longer accompanied him”. Many of the people, having only just witnessed the miracle of the Multiplication of the Loaves the previous day, left and no longer followed him because of this teaching. If Jesus was speaking metaphorically about consuming his flesh, I find it hard to believe that he would have just let them go. The people seemed to have no issue about figuring out if he was speaking literally or figuratively, and I don’t think that Jesus is really beating around the bush with this one.

In the next verse, “Jesus then said to the Twelve, ‘Do you also want to leave?’ Simon Peter answered him, ‘Master, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and are convinced that you are the Holy One of God.'”

Though the Twelve don’t yet understand the mystery of the Eucharist, they remain faithful to Jesus and believe that he has the words of eternal life even after most everyone else abandons Jesus. I find it interesting that Peter is the one speaking for the group, “the rock” upon which Jesus’ Church is built, the first pope, seems to have an understanding of his ecclesial role even before it is bestowed upon him. He speaks truly when he proclaims that Jesus is “the Holy One of God” and he is able to accept Christ’s Bread of Life Discourse in the midst of such doubt and unbelief.

Holy Communion

Now that there is context for why Catholics hold these beliefs about Christ’s presence in the Eucharist, let’s talk about Holy Communion. I think this quote from the Second Vatican Council sums it up pretty well (Sacrosanctum Concilium 47):

At the Last Supper, on the night he was betrayed, our Savior instituted the Eucharistic Sacrifice of his Body and Blood. He did this in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the cross throughout the centuries until he should come again, and so to entrust to his beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of his death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity, a paschal banquet in which Christ is consumed, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.

Okay, so what does that mean? What happens when we receive the Eucharist at Mass? To put it plainly: we become one with Christ. This little sentence, though short, carries with it an incredible weight of understanding.

When we eat the Eucharist, we become physically united with the Lord. This physical unity also brings about spiritual unity with Christ; in Communion, our soul receives the spiritual food it needs to survive just as our bodies need physical food to survive. In consuming the Eucharist, we are not only taking part in a sacramental union between our body and the Sacred Host, but we are also united spiritually, soul-to-soul with Christ. This union is what we refer to as Communion.

This unification with Christ is not limited to the person of Jesus, or even to the three Persons of the Trinity. Everyone who takes part in Communion is united with each other. Paul explains in his first letter to the Corinthians (12:27) that we, as the Church, are Christ’s body. By being made one with Christ Jesus in the reception of the Eucharist, we are necessarily being united with the mystical body of Christ which is the collection of the members of the Church. As a result of this unification with our neighbors, a person who receives Communion with a contrite heart and a disposition of thanksgiving will experience goodwill toward others, which is one of the fruits of the sacrament. The communicant will experience, over time, a reduction in racial or national prejudices and an increase in compassion and patience for the people they interact with. We are, as the Church, being taken into perfect Communion with God through the Holy Spirit in the consumption of Christ in the Eucharist.

Sacrifice?

The word “sacrifice” can be somewhat concerning to people. It can be viewed as an archaic or cultish way of pleasing the pagan gods or performing a satanic ritual. Even sacrifice described in the Old Testament is sometimes viewed as primitive and counterproductive. We tend to think that in the age of the New Testament, sacrifice has been abolished by the one true Sacrifice of Jesus on the cross. While this notion is partly true, the Catholic Mass is indeed a sacrifice; it is the Sacrifice of Christ perpetuated until his return as he instructed and as was foretold in the Old Testament.

Okay, so what the heck are we talking about here? Let’s start with some OT background: Passover was instituted by God through Moses for the Jewish people who were enslaved by the Egyptians as a means of delivering God’s people from their bondage. It was established as a perpetual celebration to last until the end of time. Exodus 12:14 states:

Now this day will be a memorial to you, and you shall celebrate it as a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations you are to celebrate it as a permanent ordinance.

Christ did indeed bring a new covenant to us from God; he himself is the new covenant and he mediates between us and God by sharing in our humanity. He did not, however, come to abolish the Passover and to instate something new. He fulfills the Passover and perfects it – he becomes the Paschal Lamb who takes away the sins of the world. One could write a book on how Christ has perfectly fulfilled the tradition of the Passover and in fact, many people have, but we will only skim the surface here in the interest of time.

Let’s go back to the Last Supper again, specifically to the part where Jesus says, “do this in remembrance of Me” (Luke 22:19). I think you know where I’m going with this and yes, we’re going to be experts at Greek by the end of this. The statement in in Greek is, “τοῦτο ποιεῖτε εἰς τὴν ἐμὴν ἀνάμνησιν,” or phonetically, “Touto poieite eis tan eman anamnesin”. We’re going to look at two parts of this statement: first, Touto poieite, then anamnesin.

The phrase touto poieit can be translated as “do this” or “offer this”. In the Old Testament, sacrifice was a common practice and had a lot to do with the way the Jewish people practiced their faith. In the Greek understanding of the OT, this word poiein was used to describe the sacrifices that were offered upon the altars of the Jews. The other phrase anamnesin means “to remember” and is commonly used in the context of a memorial sacrifice throughout the Greek OT. As we have seen, the meaning of the words is somewhat obscured in English, but the disciples, who were very familiar with the Old Testament and Jewish law, could fully and correctly understand what Jesus was telling them and could relate it in Greek when writing the Gospels.

Therefore, at the Last Supper, Jesus fulfilled the Jewish tradition of Passover, which is to last for all time, by instituting the Eucharist as a perpetual sacrifice, an eternal memorial of his own perfect offering to the Lord in atonement for our sins. This concept was understood and accepted by the disciples and the early Christian Church, and was presented in the Didache, a work that presented the beliefs of the early Church written in the first century, quoted here as, “But every Lord’s day gather yourselves together, and break bread, and give thanksgiving after having confessed your transgressions, that your sacrifice may be pure” (Didache Chapter 14).

A side note on the Didache: it is fairly short and it provides an excellent and concise summary of what the first Christians believed. It is essentially the first Catechism of the Church and was used in the evangelical efforts of the apostles to spread the faith in a consistent manner. You can find it here: Didache. If you would like more accounts of the beliefs of the early Church, click on this link to view an article that quotes thirteen different sources.

Now, let’s get into some detail about the Sacrifice of the Mass. First and foremost, there is no killing involved in the Sacrifice of the Mass. A sacrifice in the context of the Old Testament is the act of offering something by a priest to God alone. There have been many different types of offerings including fruits, wine, animals, and bread. One type of sacrifice was called the “wave offering” and was an unbloody sacrifice made by waving the gift before the Lord. Setting these things aside as a gift to God signifies that God is the Master of the world and that his people are dependent on him.

However, none of these Old Testament sacrifices were sufficient for the redemption of the world. As a result, God himself, through Christ Jesus, had to make the only sacrifice worthy of redemption for all people; he gave his only son as the spotless victim of the eternal Passover Lamb.

A priest, traditionally defined, is a person who is consecrated to be a mediator between God and people, and in the Old Testament, priests were the ones who performed sacrifices. The Catholic priest is In persona Christi, or “in the person of Christ”, as he says the words of consecration in the reenactment of the Last Supper, but the principal priest at every Mass is Christ himself. Jesus offers himself to his heavenly Father through the ministry of the ordained priest celebrating the Mass.

A good distinction to make at this point is that the priest is not commanding Christ to come down from Heaven so that he may be sacrificed again and again at each Mass. Men do not posses the power to command God, and suggesting that he is killed over and over would be to say that Christ’s one true sacrifice was in some way deficient. Rather, by his love for us and his will to be united with his Church, Jesus is acting through the priest as Jesus presents himself as the perfect and eternal sacrifice to God the Father.

So what’s the difference between the sacrifice on the cross and the Sacrifice of the Mass? The answer to this is that they are really the same sacrifice, but presented in different ways. They are the same in that Christ Jesus is being offered in atonement for the sins of the world and it is Jesus himself who is acting as the principal priest, but the manner in which the sacrifices are offered is different. On the cross, Jesus physically suffered, shed his blood, and was killed. The sacrifice on the Cross is analogous to the Passover lamb which is slain and its blood shed. The Sacrifice of the Mass on the other hand, is analogous to the wave offerings we discussed previously. In the Mass, the resurrected body and blood, soul and divinity of Christ is offered to God in an unbloody manner, in the form of a living sacrifice. The living and resurrected Jesus is presented before the Lord and given up as the sacrament of the Eucharist in thanksgiving to God. The word “Eucharist” is derived from the Greek word εὐχάριστος (eucharistos) meaning “grateful” or “thanksgiving”.

The Sacramental Nature

What is a sacrament? This is a topic for a different time, but in short, a sacrament is an outward and visible sign of inward and spiritual divine grace which was given to the Church by Christ in order to confer grace upon the people. The seven sacraments administered by the Catholic Church are baptism, confirmation, Holy Eucharist, penance, the anointing of the sick, holy orders, and matrimony.

The principal purpose of receiving the Eucharist is to increase sanctifying grace through the personal union with God, who is the giver of grace. That sounds like a positive effect, but what exactly is sanctifying grace? Simply put, sanctifying grace is grace that stays in one’s soul; it makes the soul holy and gives supernatural life. To sanctify something is to make it holy, and to have a holy soul through life and into death is basically the goal of the Christian life. So it stands to reason that by the reception of the Eucharist, our souls are made more holy by an increase of sanctifying grace which is why the Mass is “the source and summit of the Christian life” (Catholic Church 1324). The Holy Eucharist is the sacrament of spiritual growth and leads to an increase in the strength of one’s soul; it is, in every sense, “soul food”.

Why Can’t Everyone Receive?

This is a tough question to answer gracefully and I’ll do my best here. We live in a culture of inclusivity, a culture where everyone gets a trophy – if a group of people is doing something that is not totally inclusive of everyone else, and if there is any sort of perceived inequality between the members and nonmembers of that group, the whole thing is written of as “hateful” and there is given no opportunity for justification. While there are a few requirements to receive communion (there are some for Catholics too, not just non-Catholics), I am in no way trying to exclude anyone from being exposed to the Eucharistic Celebration of the Mass. People from other faith traditions, both Christian and non-Christian, are welcome to any Catholic Mass and I would encourage everyone to attend just to see what it’s all about. Catholics, I would encourage you to invite your non-Catholic friends or those who have fallen away from the faith. After all, “if we walk in the Light as He Himself is in the Light, we have fellowship with one another” (1 John 1:7).

The most basic requirement to receive Holy Communion is Christian baptism. This sacrament wipes away the stain of original sin and is the rite of initiation into the Church. Baptism, by its nature, impresses a permanent and everlasting character on the soul; it gives a person the right to receive the sanctifying graces given in the Eucharist. Sanctifying grace renders one as an adopted child of God and confers the right to heavenly glory. It is by baptism that the soul is emptied of original sin so that it may be filled with sanctifying grace so that we may be united with God.

Since baptism is performed “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”, faith in Jesus Christ as the son of God, he who takes away the sins of the world, is required for baptism and therefore required for Communion. The U.S. Council of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) gives the following Eucharistic guidelines for non-Christians:

We also welcome to this celebration those who do not share our faith in Jesus Christ. While we cannot admit them to Holy Communion, we ask them to offer their prayers for the peace and the unity of the human family.

Christian baptism is not the only requirement, however. The communicant must also profess the Catholic faith and everything the Church teaches, including Transubstantiation. Holy Communion is an outward sign of unity of the Catholic faith, and those who are Christian, but not Catholic are not in communion, or united with, the Church. Therefore, to receive Communion as a non-Catholic would be a dishonest action of the recipient. A bit more drastically, we hear from Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians (11:29), “For he who eats and drinks, eats and drinks judgment to himself if he does not judge the body rightly”. The USCCB states for our fellow Christians:

We pray that our common baptism and the action of the Holy Spirit in this Eucharist will draw us closer to one another and begin to dispel the sad divisions which separate us. We pray that these will lessen and finally disappear, in keeping with Christ’s prayer for us ‘that they may all be one’ (John 17:21).

It is not enough to simply profess the Catholic faith to take part in Holy Communion since that does not directly imply eligibility. In order to receive the Eucharist, one must be in full Communion with the Church, that is, one must be free from mortal, or grave sin. The Catechism of the Catholic Church describes sin as “an offense against reason, truth, and right conscience,” and states that “sin sets itself against God’s love for us and turns our hearts away from it,” (Catholic Church 1849-1850).

Without getting too far into this topic, there are two types of sin: “venial” and “mortal”. Venial sin is still sin, but allows for charity to subsist in the soul, even though it wounds and offends it. Mortal sin, however, is more serious. It is a “sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent,” (Catholic Church 1857). Through such a serious transgression, one who commits mortal sin is turning their back on God which disallows grace to be bestowed upon them. By committing mortal sin, the relationship between a person and God is severed, and thereby severs the relationship between that person and the Church, who is the mystical body of Christ. This brings us back to the idea that in order to receive the Eucharist, we must be united with the Church, and in order to make such a public display of unity, we must be in Communion with those who are also making that same display. The damage of mortal sin is only repaired through the sacrament of confession which forgives the sins and places the soul of that person back into Communion with the Church.

Therefore, one’s soul must be in a state of grace in order to receive Communion. This state of grace is achieved after baptism or after Reconciliation if one has sinned, and furthermore, this state of grace is built up by the increase of sanctifying grace we receive in the Eucharist; so by receiving it, we are strengthened in our conviction to stay true to God, to be free of sin, and to live out our call to be holy men and women of God.

Conclusion

I hope I have done a sort-of-okay job at covering the inexhaustible and never-ending topic of the Holy Eucharist. I really think that the more one studies the Eucharist, the more one finds things to learn. It is one of the most intricate and fascinating mysteries of the Catholic faith and I hope that this has shed some light on the subject. It’s easy to see why the celebration of the Mass is “the source and summit of the Christian life” and I pray that one day, the whole world will be united in faith and love for Christ Jesus who gave his life for us and who remains with us through the perfect gift of the Eucharist.

Thank you for your fine exposition of the Roman Catholic understanding of the Eucharist. I do have three suggestions. (1) that you add some comment about the two other modes of Christ’s presence besides in the elements and the person of the presider, namely, the proclaimed Word and the assembled people. Also it would be good, me thinks, if you mentioned the conditions under which a Christian not in full communion with the Church can licitly receive Communion, And finally I suggest you read up on the current consensus among exegetical scholars on the meaning of the Greek word, “soma” in the Eucharistic tradition Paul transmitted in his first letter to the congregation at Corinth.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, John. You are right about the other forms of Christ’s Body, and much more could be said on the subjects – perhaps an exercise for the future.

Non-Christians, non-Catholic Christians, and even Catholics who are in a state of grave sin are asked to abstain from the Eucharist. Now, this is a difficult thing to bear especially when we would like to promote a sense of inclusion rather than exclusion (https://catholicphysicist.com/2017/07/06/what-does-catholic-mean/), but the Church has good reasons for Her stance on the subject. Under almost every circumstance regarding the reception of the Eucharist by a person not in full communion with the Church, it is proper to abstain. However, there are some very extraordinary circumstances in which a person can licitly receive. The first and easiest to deal with are Christians belonging to the Orthodox churches, the Assyrian Church of the East, and the Polish National Catholic Church; though not in full communion with the Roman Church, these Churches have valid Holy Orders and valid Eucharist (see Canon Law 844 §2-3). The second, and much more uncommon circumstance requires the approval of the diocesan bishop within the provisions of Canon Law. Subsection 4 of Canon Law 844 states, “If there is a danger of death or if, in the judgement of the diocesan bishop or of the episcopal conference, there is some other grave and pressing need, Catholic ministers may lawfully administer these same sacraments to other Christians not in full communion with the Catholic Church, who cannot approach a minister of their own community and who spontaneously ask for them, provided that they demonstrate the Catholic faith in respect of these sacraments and are properly disposed.” These are indeed very extraordinary circumstances. A baptized, non-Catholic Christian can receive, but must be in a grave and dire situation, and must have a demonstrated understanding and willful acceptance of the Church’s teaching, and must be unable to receive the pastoral care of their own minister. This is a poignant article on the subject: https://www.catholic.com/magazine/online-edition/non-catholics-in-the-communion-line .

Phew… And finally, you’re right again; “soma” is an especially interesting word that gets mixed up in this topic as well as the others you’ve brought up. Thank you for your thought-provoking comment.

Ad maiorem Dei gloriam,

Max

LikeLike